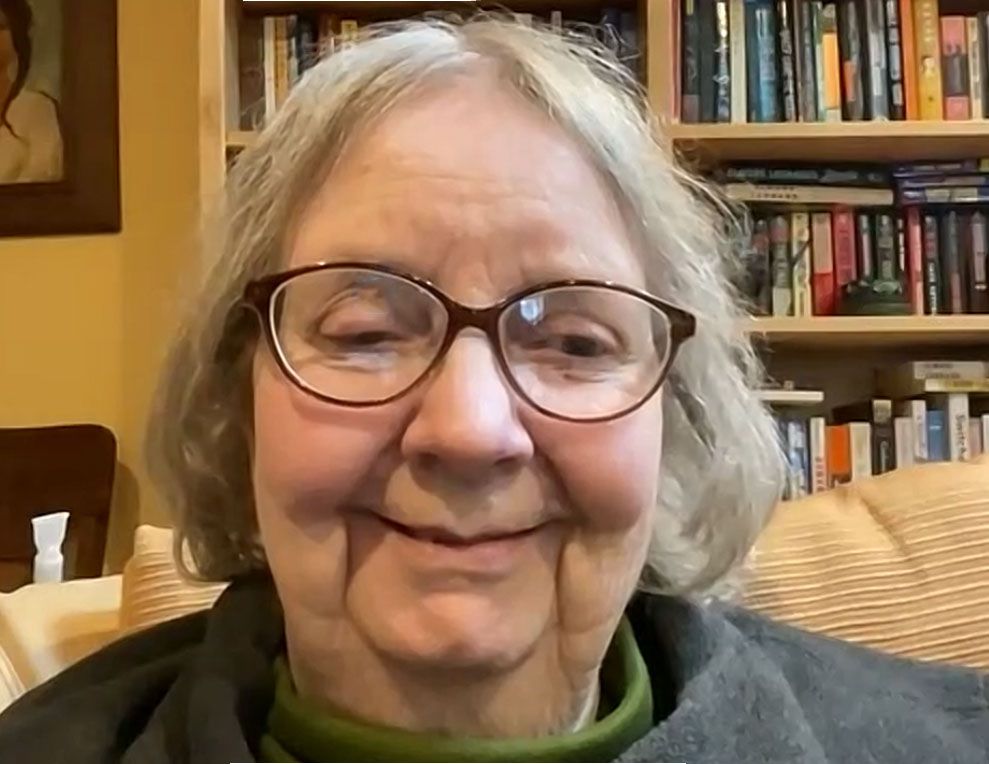

An Interview with Anna Willman, in conversation with Dana Hercbergs

I met Anna in 2021 through the Focusing community and occasionally attended her weekly Saturday Listening Space, an online peer support group. Her facilitation style melds her own grounded attention with her wonderful sense of humor.

The overarching theme of this interview was the ethos of respect and egalitarianism that imbued all aspects of her work at the Confidence Clinic, a community wellness program for low income women in Roseburg, Oregon. During her 18 years there, Anna facilitated many group sessions.

The Confidence Clinic program staff was trained to treat program participants’ confidential information with utmost care and to consider them their equals. The staff were called “program coordinators” rather than “teachers” as the expectation was that everyone – staff and participants alike – would be both teachers and learners.

Three of the important components of Anna’s approach at the Clinic were handling conflict in groups, balancing people’s needs and allowing space for growth, and confidentiality.

Handling Conflict in Groups

What stood out in our conversation about group facilitation was Anna’s skillful handling of conflict, using listening, resourceful problem-solving, and setting clear boundaries. She described how her “worst and best” group experience unfolded on the first meeting of a small group session.

“Almost before the group members had settled into place, one woman accused another of stealing her food stamps. I took a big breath and went into communication problem-solving, getting-them-to-listen-to-each-other-mode.”

Anna began by establishing the facts. The woman who had accused her peer of stealing food stamps from her purse had left it unattended in the classroom to go outside to smoke. The accused woman did not join the others outside, but denied taking the food stamps.

“Did you actually see her take the food stamps?” No, the accuser did not. Nor had anyone else in the group. With no way to prove it one way or another, Anna moved on to listening. “What are you feeling? Can you tell me what you hear the other woman is feeling right now?”

The group agreed that it was terrible to lose all your food stamps – and terrifying to be accused of taking them. They then turned to problem-solving. Anna started by wondering why someone might be tempted to take the food stamps. “We don’t really know what problems other people are facing. But I imagine if someone had hungry children at home, it would be hard to resist taking food stamps when such an opportunity presented itself. It might be kinder not to put anyone to that kind of test.” Again there was group agreement, and everyone said they would take responsibility for safeguarding their belongings.

Next, Anna posed this question to the group: “What can we do from here?” And she asked the woman who had lost her stamps, “How can we help you?”

One of the women in the group then opened her purse and gave the woman $5. Another gave her $20 in food stamps. Then everyone started donating one way or another. In the end, the woman came away with more money for food for that month than she had lost.

What started as a potential catastrophe became a group bonding experience.

Balancing People’s Needs and Allowing Space for Growth

Asked about advice for group facilitators, Anna stated the importance of balancing the needs of individuals in the group with the needs of the group. How a facilitator interacts with one individual affects the group as a whole. “If you respond brusquely to someone, that will shut everyone else down, especially the quiet ones.” Anna advised using the facilitator role to keep the process respectful to everyone involved, including any disruptive person.

She told Marissa’s story. Marissa arrived at the Confidence Clinic determined to “do it right”. She was bright, attentive, and enthusiastic. Whenever a question was asked, she was the first to answer. When we suggested people raise their hands before answering, she waved her hand wildly in the air, demanding to be called upon. When other participants whispered to each other in side conversations, she shushed them loudly, even scolding them for not taking the program seriously.

Sometimes people behave in ways (like Marissa was doing) that naturally set them up to become the group scapegoat. Anna did not want this to happen to Marissa.

She called her aside during a break and asked about how she felt the group was going. Marissa had a lot of criticism for Suzy, who she thought didn’t pay enough attention in class. Anna wondered if Marissa thought her own behavior might be irritating some of the women, and Marissa said she didn’t care how other people felt so long as she herself learned everything she could.

Anna thought for a moment and then said, “I think I know how you feel. When I am excited about learning new things, sometimes I get carried away and talk too much. I interrupt people and dominate the group. It feels pretty good at the moment, but later I find I missed out on something because I was talking instead of listening. Maybe if you don’t try to answer every question and give others a chance, you could learn something valuable. Maybe you could learn something from Suzy.”

“I don’t want to waste my time,” Marissa said. “I came to learn from you.”

“When you raise your hand at every question, you’re closing the door for shy people. I’m hoping you will make space for them.”

“Well, I’ll try.”

After several conversations, Marissa made an effort not to dominate the group, but often she did it by visibly holding her arm down and grimacing with the discomfort of not speaking. Eyes rolled. She was still irritating the other participants.

We talked. “How did that feel for you? What can we do to help you do this better?”

Then one day Anna said: “Marissa, I love how much you want to just absorb everything that happens here. And I’m concerned that you’re missing one of the most important parts of the program, a part that you could learn from Suzy.”

Marissa: “What do you mean?”

Anna: “Well, a key part of this program is the group process, being part of a group and building a network of support among the women. And you’re not getting it because you only want to learn from me and the coordinators. You could learn from Suzy—she may not feel comfortable talking to the whole group like you, but her side conversations and laughter are her way of participating. She’s working hard to make friends and fit in.”

For the first time Marissa seemed to respond. She really didn’t want to think she was missing something. “But it’s too hard. And people are already mad at me.”

“Maybe you could share with the group how hard this is for you. Ask them for support.”

Marissa: “They’ll laugh at me.”

Anna: “Maybe.”

That afternoon Marissa said to the group, “I’m trying not to dominate everything. This is really hard for me. I hope you will help me.”

The whole class fell in love with her. “You go, girl!”

They supported her throughout the sessions. Her participation was always strong, but, as time went by, she spoke less and listened more. She began to take lunch breaks with Suzy. At the end of the session, the group voted her “most improved”. She organized a monthly follow-up, where members of that session met to watch video tapes of “Sex in the City”.

Marissa risked being honest and open about what was going on for her and it worked! “Most of the time people are kind,” Anna said, “but it’s hard not to scapegoat someone who seems to be asking for it. Still, my experience tells me that the group will almost always give someone one more chance.”

By talking honestly to Marissa and listening to understand what was happening for her, Anna showed respect and trust in her ability to choose wisely. The group’s needs were met and the individual gained self-confidence and autonomy as well as important group skills.

Confidentiality

In the small town where the Confidence Clinic operated, confidentiality was addressed directly early on in the program. Coordinators won the participants’ trust by never disclosing information to funders or agency partners beyond what was essential. Attendance records were shared with referring agencies, but nothing about a women’s issues or behavior without specific permission from the woman. And even then staff made sure that the woman was present whenever her case was discussed with another program’s case worker so that she would know exactly what information had been shared.

If anyone called to ask for a woman, the staff would first ask that woman’s permission before responding to the caller.

“We always told women the truth,” Anna said. “Whether it was about personal hygiene or dominating behavior in the classroom, they knew they could trust us to tell the truth – and always in a kind and gentle way.”

Finally, confidentiality in the group was inspired by prompting the women to respect their own boundaries so that they never felt compelled to share anything they did not want to, even if asked. This struck me as a way to honor each person’s autonomy by placing responsibility for their safety within themselves first.

In a recent Focusing workshop “Fear can be a Friend,” the message was reiterated that safety was something we can take control of by checking inside, “Do I feel ready to share this?” And, if not, we do not have to tell the story, but we can check the felt sense of the story, and relate that. This is the beauty of Focusing.

Anna is a joy and an inspiration to learn from. As a student of social work, she is eager to carry forward her approach of listening, respect, and practical problem-solving in my meetings with people, clients and colleagues, and to live the questions of ethics, boundaries, and freedom. She also recognizes that this will take much time and experience.

Note: Anna Willman’s book about her work at the Confidence Clinic is called “Creating Confidence: How to Do Social Work Without Destroying People’s Souls” and is available on Kindle and as a hard copy on Amazon.com.