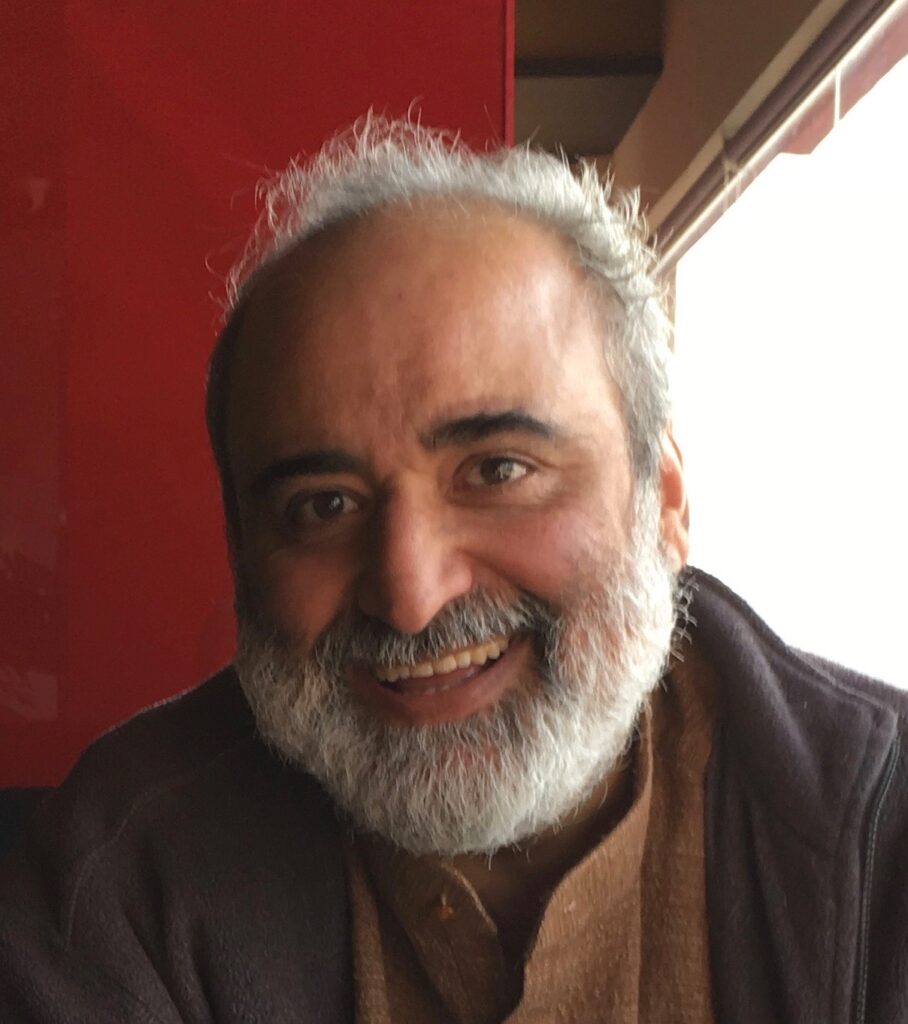

Syed Wajid has a round face and a trim white beard and a smile that lights up his eyes and warms the hearts of his companions.

Child labor is a huge problem in Pakistan, he tells us. Some provincial governments have passed laws forbidding the employment of children, but these laws are not enforceable. The root problem is deep, widespread poverty, which has become even worse since the onset of the pandemic.

When you are hungry, you will work in order to eat and to feed your family, no matter how young you are. If you are an employer, also poor, struggling to survive, you will hire the cheapest workers you can find. And when families are unable to afford school fees, the children who work are at least kept busy during the day, while those who do not have anything to occupy them and no hope of escaping their hunger become vulnerable to radical forces who tempt them to sacrifice themselves as drug traffickers and suicide bombers in exchange for promises to keep their families fed.

Laws banning child labor, though well-intended, merely add a new opportunity for corruption and a “tax” that the already struggling businessman must pay to the visiting inspector to overlook the children working in his bakery, his auto shop, his market stall.

So Wajid has envisioned a different approach. One that works with the system as it is, and that gives the children an opportunity to learn even while they work. BRIGHTER TOMORROW is a project that gives working children a meal and a curriculum that is designed just for them, not only to give them literacy and numeracy, but to prepare them to return to school full-time when times get better and school fees can once more be paid.

BRIGHTER TOMORROW is just Wajid’s latest project. FII co-director Pat Omidian first met him when he attended a self-care workshop she was giving for exhausted rescue workers after the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan.

Wajid has been on the frontlines for decades, working to alleviate suffering from domestic violence, poverty, natural and human-caused disasters, and social injustice in Pakistan. Sometimes he is paid. Much of the time he volunteers.

“It brings me joy and it brings me tears, too.

When I work with vulnerable children, with women, with families,

there is joy and there are tears.”

When asked what motivates him to keep doing this kind of work, why does he do it, he flashes that warm smile, “Why shouldn’t I?” he asks.

His uncle studied in the United States and got a doctorate in science. But instead of staying there, he returned to Pakistan after 1947. His professor told him, “You won’t even find a test tube there!” And his uncle replied, “That’s precisely why I am going back.” His father was a doctor who studied in the United Kingdom, and was even legally a British national. But he, too, returned to the new Pakistan because he wanted to help make the change.

Wajid follows in his father’s and uncle’s footsteps. He has chosen to stay in Pakistan and put his energies into helping his people.

“I grew up living with my father and my uncle and all their dreams. So all I am doing is trying to take those dreams forward,” Wajid says. “I know what it feels like to be with an empty belly. My elders came from a poor background. They were not rich, and it was education that changed everything.”

“Why am I doing this? It’s either in the genes or the momentum they started. For me, what I’ve seen is that money is important, but only to an extent. Beyond that you go empty-handed. So it’s better if things are rolling on.

It’s something I like to do for me. It’s a hobby where I’m spending my free time, and not spending money. If my hobby was going to horse races, I would be spending money. I think it is a more productive hobby when you give.

It brings me joy and it brings me tears, too. When I work with vulnerable children, with women, with families, there is joy and there are tears.”

And as he finishes speaking, Wajid’s face lights up with a smile and his eyes glisten with tears.